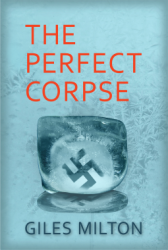

An interesting case brings foresic archaeologist Jack Raven to the small town of Henford, Nevada. In the Greenland ice, a perfectly conserved body has been found which must belong to a Ferris Clark who was stationed there as a meteorologist during the Second World War. Now, an American company which experiments in freezing people to conserve them for a time in the future wants to experiment with the body. Tammy Fox, one if the scientists, is not happy with their plan and has therefore invited Jack who already worked on frozen bodies. The experiment seems to work well, but suddenly, in the middle of the night, the corps wakes to life, much earlier than anticipated. Not knowing what happened to him, he gets up to complete his mission which consists of getting rid of a couple of people. The scientists are alarmed when they find this out since their experiment was not meant to attract any publicity. And there is another problem : the re-awakened murderer is not who they thought and a lot more dangerous than they could ever imagine.

When reading the short description I had some doubts of how the elements could be linked convincingly. Yet, they all add a to a fast-paced thriller with a lot of twists and turns and constantly new aspects which are well motivated. Thus the plot follows a red thread and the story could convince me. Even though some parts are quite foreseeable, I felt well entertained while reading it.

Nevertheless, I could have done without the obligatory love story in the novel and Jack’s background story as an alcoholic also did not really add any relevant information to the plot. I also did not make the character more round for me, therefore, I would have preferred sticking to the story and having less emotional fuss. Even though I found the link between the past and the present convincing, I guess most of it was a bit far-fetched and exaggerated, also the scientists’ work, I hope that we are still far from what they could do in the novel.